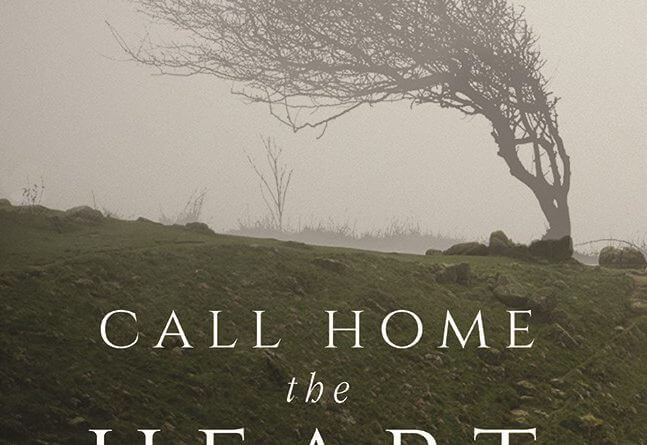

‘Call Home The Heart’ An Extract By Sally Wragg

A thunder cloud hung over Nethermere. November had arrived with a storm this year, whipping the leaves from the beeches at the bottom of the dell and sending spiteful gusts of wind howling along Wolfstone Valley. Laurie Beck thrust chapped fingers into his pockets and glared at his father, kneeling to repair the damage caused by the flock, sent senseless by the proximity of a fox, bolting as one and not stopping to let a little obstacle like Scalp Edge wall stand in their way.

Gabriel Beck heaved a low, flat stone from the heap of stones at his side and shoved it into position. He squinted up at his son.

“Thee’s not much to say for thee’sen this mornin’,” he observed, conversationally. Lawrence thrust out his bottom lip. “Have we finished yet, father?”

“No, we have not, lad.” Gabriel pushed his cap to the back of his head with a grizzled thumb, a hard, plain-looking man, hewn out of the craggy rocks with which the white peaks abounded and yet with a certain softness of expression more true to the nature housed within his wiry frame. Seeing the boy’s gaze wander, yearningly, back towards the farmhouse, a ramshackle, dilapidated pile of old Derbyshire stone nestled on the hill-side, the old man sighed.

Becks had been tenants of Nethermere Farm for generations.

“Happen its time we stopped for a bite to eat…” The words were no sooner out of his mouth than Laurie, turning smartly on his heels, began to hurry away down the slope of the valley. “Tell thee mother I’ll be down shortly!” Gabriel bellowed after him, unsure whether he’d been heard or not. Blast the boy! Dealing with their Laurie was like batting his head against a brick wall, he conceded, too sadly used to it. He had no idea what had got into the lad this morning, spooning around like a streak of useless tap water but there, that wasn’t unusual.

He reached for another stone.

Laurie felt only elation. Elation he’d got away from the bitter, biting wind, part and parcel of this exposed part of Derbyshire and aye, elation he’d got away from his father too, though the old man meant him well and had never lifted a finger to him, not even when he’d left the gate open to the pig pen and Sadie, the bad-tempered old sow, had got into the barn and eaten a month’s supply of feed. His father put up with a lot and complained little, Laurie acknowledged. But that was his way, as it was Laurie’s to do the opposite of what anyone expected, driven by internal forces over which he had no control. Laziness, indifference, a desire to concede as little ground as possible, at loggerheads with his father’s efforts to involve him in the farm when he patently wasn’t interested and worse, never would be. There was a world beyond Hartswell and he longed to find it. Why wouldn’t his father leave him be and accept that his son, even at this young age, had no intention of taking on the farm when he grew up, turning himself into another tool by which their landlord, Squire Ralph Blaze-Drummond, should stuff his pockets with money! Dimly aware of a bird trilling atop the twisted stump of an ash tree, so common to this part of the world, Laurie quickened his pace. Farm work bored him. His father bored him and if he wasn’t old enough to realise it yet, some instinctive consciousness of the fact lent strength to his swirling emotions. A sturdy, inward-looking boy of fourteen years of age, with prominent cheekbones, a scowling expression and a shock of wavy, dark hair, with hints of auburn, just like his mother’s.

Thoughts of Clara, his mother, only deepened his gloom.

He was nearing the farmhouse building, and neatly vaulting the gate into the yard, he hurried inside, where from its basket, by the fire, a black and white collie rushed to greet him. With a surprising gentleness, Laurie stooped to fondle its rough fur, raising his head in time to view a sight which brought him up as sharply as if someone had thrust a knife into his ribs. A scene he’d witnessed near enough as long as he’d memory to remember it – his mother tipping out the day’s bread from the oven onto the rack on the kitchen table and Wilfred, his younger sibling by two years, sitting by her side, pouring over his school books, spread out on the table before him.

The kitchen was redolent of the morning’s bread and the bacon scraps his mother had fried for their breakfast, mixed with the faint aroma of dried lavender and camomile she turned into soap for household tasks. Unlike Laurie, Clara Beck was practical, her hands, if surprisingly slender, rubbed red raw with housework. A slightly boned, attractive woman, past the first flush of youth, whose face bore signs of past troubles neither son had ever fathomed; Wilfred because he wasn’t old enough and Laurie because, try as he might to alter the status quo, their natural relationship was to be at loggerheads. As he watched, frozen into a tableau of despair, Clara ruffled Wilf’s hair. And then she saw Laurie and a flicker of unease crossed her face, replaced too quickly by a smile that twisted the boy’s insides. An angry retort arose, unprovoked to his lips which long practice had taught him to stifle.

“There you are,” she murmured, easily enough, for she’d had long practice too. “And where’s your father? Have you two finished?”

“Father says he’ll be down shortly.” “You’ll be ready for summat to eat…”

Clara Beck was already moving towards the pan of broth simmering on the stove. A sullen look crossed Laurie’s face. Tight-lipped, he crossed the room and ducking his head under the tap at the stone sink, an action bound to provoke, he drank thirstily. He straightened up, gloatingly wiping a grubby hand across the back of his mouth. A dribble of water ran down his chin.

“I’m not hungry.”

Giving her no chance to engage him further, he flung away outside, slamming the door behind him and imagining her vexation with satisfaction. She could do nothing with him. No-one could and that was just the way he liked it. Aware only of the need to put distance between himself and the farm, once on the other side of the gate, he began to run, long, loping strides that ate up the ground and made his breathing grow ragged. His mother and Wilfred, Wilfred and his mother, a mutual admiration society with his father hovering uneasily on its perimeter. And Laurie, nowhere at all, like an apple tossed out of the barrel and left to rot. The wind cooled his heated cheeks. Swinging wildly away from the farm, he headed out towards Snake Pit, a large round lake of natural water which collected on a plateau above the valley side, used by the local farmers to water their stock. Heading determinedly past it, he struck out towards The Whims, a copper mine long since fallen into disuse, its presence still a draw to the boys of the district, Laurie included. His pace slowed and he shoved his hands into his pockets, walking on moodily, his feelings dissipating into something more manageable. He was resentful, confused, vaguely ashamed of himself and contritely, thinking now of how hurt his mother had looked when he’d stormed out.

She’d only herself to blame. He’d reached the top of the ridge beyond which was the open shaft of the mine, the ground immediately before it littered with twists of tortured metal, indicative of days gone by when copper mining had been a thriving industry around these parts. He had no desire to venture home yet. With sense enough to stick to the path, thus avoiding the concealed open shafts so dangerous to unwary travellers, he walked on, past the gaping face of the mine. The incline steepened. Why did the sight of his mother and Wilfred together upset him so? It wasn’t anything their Wilfred had done – as if he wanted his place on the pedestal where their mother had placed him. Laurie felt sorry for him, his mother making such a fuss over him, even his father said she’d make a milksop of the lad.

A huge granite stone heaved itself into sight, rising up out of the ground as if some giant’s hand had hurled it there, an eighth century Celtic Cross, near enough a man’s height, a ghostly sentinel dominating its surround, known locally as The Standing Stone. A connection with an ancient race and Laurie had often pondered on its significance. There was a path leading from it into a copse of trees and instinctively, he followed it, plunging into its shadowy depths, his gaze caught and drawn by a flash of orange-red he thought at first he must have imagined. But no, there it was again. His breath caught in his throat. The boy had never seen a fox at such close quarters before, pinned to the mast as it were, though he’d glimpsed one now and then around the farm, a sense often only manifested in Tess’s low growl and her hackles rising. The creature was injured, dirty and emaciated, its rib-cage prominent. It had black socks and a whitish underbelly and a grey-white tip at the end of its brush. Spots of blood tracked its progress and it was limping, its body a taut line of pain. It must have been starving, for it had been injured a while, he reckoned. There was a sense of hopelessness about it as it slunk along, not acknowledging him though it cast him furtive glances, as if it was on the point of giving up and was telling him so in the only way it knew. As he watched, scarcely daring to breath, it disappeared behind a clump of loose earth at the base of a tree trunk, into its burrow, or whatever a fox’s home was called, a lair, wasn’t it? For long, tortured seconds he waited, then cautiously made for the spot where it had disappeared, reaching it without mishap and squatting down on his haunches to lean forwards, peering past the mound of earth and beyond, into what he saw now was an entrance hole, leading down into darkness. A stench of something rotten, as of meat gone bad, rose to greet him and from which he recoiled. He tensed, half expecting it to leap out at him but nothing so unlikely occurred. Seconds passed and encouraged, he moved nearer, until by moving his face up close, he could see into the opening. A pair of luminous green eyes glared back at him.

“Dunna worry… I wunna hurt you,” he crooned, wanting instantly to comfort it and show it that he meant it no harm. It was dying, he could see it in its eyes which seemed to him full of sorrow. What a wise creature, talking to him in a way beyond words. He didn’t want it to die.

“Wait…wait I’ll be back wi’ some food. Don’t you dare die on me…” He rose to his feet and backed, far enough until he’d put distance between them and then, spinning on his heels, he belted back the way he’d come, up onto the path by The Standing Stone and on, heedlessly past The Whims and The Snake Pit, all the way back to the farm, startling his mother, on her way to the barn to fetch fresh grain for the hens, squabbling in the yard.

“Why, whatever’s the matter with the lad now,” she demanded, throwing him a troubled look as he rushed on past her. Inside, Wilfred was still engrossed in his books. The boy glanced up as Laurie ran in, watching curiously as he disappeared into the pantry, only to emerge moments later with half a loaf of bread and the tired remnants of a mutton joint, the whole of which he wrapped in a cloth, deftly knotting the corners together. If his mother noticed that the food was gone, he’d tell her that he’d eaten it. He was always hungry. Everyone knew boys were always hungry.

“What are you up to, our Laurie?” Wilfred demanded. “Never you mind.”

“Is it because yer’ missed yer’ lunch? Where are you goin’ wi’ it? Can I come?”

“No you can’t, leave me be,” he retorted in a voice brooking no argument, even to Wilfred who would have followed him anywhere.

It had started to rain, freezing drops of water rattling off the roof of the barn and dashing painfully against his face. He didn’t even notice it or his father, walking down from the fields for a belated lunch. Desperate to be away, his ill-gotten gains clutched against his chest inside the protective covering of his jacket, Lawrence vaulted the gate and began to run, back towards the Whims. Would the fox have gone, seizing on the opportunity to slink off like the wild creature it was? Instinctively, he knew it was in too much pain to care what happened to it, the thought filling him with such pity, his desire to help it temporarily became his reason for being. Its image was seared into his mind. It was beautiful, its flame of life too fragile to be so easily extinguished, not if he could help it!

As he approached the entrance to its lair, he squatted down and talking to it soothingly the while, with trembling fingers, he undid the knotted cloth and tipped out the food. Then he retreated, to sit with his back against a tree trunk, affording him good view. Long minutes passed, time in which his muscles screamed in protest but after all, he hadn’t so very long to wait. He blinked and there it was, a streak of emaciated orange-red fur, its ears pressed close against its head, darting anxious looks his way before turning on the food. With a low bark, a rumble that started deep within its belly and ended with a strangled yelp at the back of its throat, it pounced and with its sharp teeth, began to tear at the meat, gulping chunks down whole. Lawrence sat on, unable to move, scarce breathe even. He’d bring it food as often as he could. He would save it, he would! And then, to his sorrow, without another glance in his direction, it vanished, back into its lair. Every scrap of food was gone. A warm feeling stirred inside him that what it had eaten had done it good – that he had done it good. Exulting in the success of his mission, he scrambled painfully to his feet. “I’ll be back tomorrow, dunna worry,” he crooned softly towards it. Sure now that not only would it have heard him but more importantly, it would have understood him too, he headed swiftly home.

Writer Sally Wragg, a lifelong Belper resident, has had short stories and serials published in magazines and books by Robert Hale and Ulverscroft Large Print. Her works are largely inspired by the striking natural landscapes of Derbyshire county and many of the settings may be familiar to our readers. Her fictional village of Hartswell in ‘Call Home the Heart’ is inspired by Hartington and its surrounding countryside.

‘Call Home The Heart’ is available now to buy from Amazon.

In story photographs: Emma Clinton

GDPR, Your Data and Us: https://nailed.community/gdpr-your-data-and-us/